Periglacial Processes

Mass movement processes are very active in periglacial areas and help to shape the landscape in areas where there is gentle relief.

Frost creep is common in the top 50 centimetres of soils in summer on steep slopes.

Ice crystals in the soil push up stones and soil particles which collapse back when the ice melts. In this way the stones and soil particles zigzag their way down the slope moving perhaps 20-30 centimetres in a year.

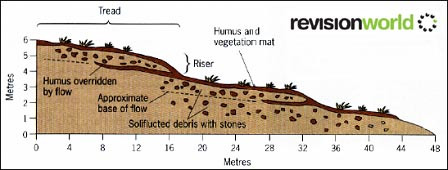

Solifluction (sometimes known as gelifluxion) is a more obvious process as it operates on a larger scale.

In the short summer season, the saturated active layer sits on top of an impermeable frozen layer. The active layer is unstable on even quite gentle slopes of 1-2 degrees. As a result of this, the active layer becomes mobile, particularly in spring, and can flow large distances.

The thin vegetation layer sometimes restricts movement but often breaks.

Frost Heave

In general, the periglacial processes remain poorly understood and there is debate as to whether the processes were more active in the past than now.

An increasing amount of research has been done as humans have tried to exploit the resources, particularly oil, in these difficult environments.

An important process in periglacial areas is frost heave. This results from ice crystals or ice lenses forming in fine-grained soils. As the ice expands, the ground above is domed up and stones get pushed to the surface.

Frozen ground cracks and forms patterned ground in which loose stones fall into the cracks to highlight the outlines.

These so-called stone polygons vary from 1-5 metres in diameter. On slopes above 2°, the stone polygons become stretched and may form stone stripes.