Long-Run Aggregate Supply

This section explains Long-Run Aggregate Supply (LRAS) covering, Introduction to Long-Run Aggregate Supply, Different Shapes of the Long-Run AS Curve, Classical LRAS Curve and Comparison of the Keynesian and Classical LRAS Curves.

Introduction to Long-Run Aggregate Supply (LRAS)

Long-Run Aggregate Supply (LRAS) represents the total quantity of goods and services that an economy can produce when all factors of production (such as labour, capital, and technology) are fully employed, and the economy is operating at its potential output. The LRAS curve is a crucial component in understanding the economy’s capacity to produce goods and services over the long run. In contrast to the short-run aggregate supply (SRAS), the LRAS is not affected by the price level but by changes in the economy's productive capacity.

This revision guide covers the shapes of the LRAS curve (Keynesian vs. Classical), and the factors influencing LRAS, including technological advances, changes in productivity, education and skills, government regulations, demographic changes, and competition policy.

Different Shapes of the Long-Run AS Curve

There are two main theories that describe the shape of the LRAS curve: the Keynesian model and the Classical model. These theories reflect different views on the economy’s capacity to produce goods and services and how the economy reacts to changes in demand.

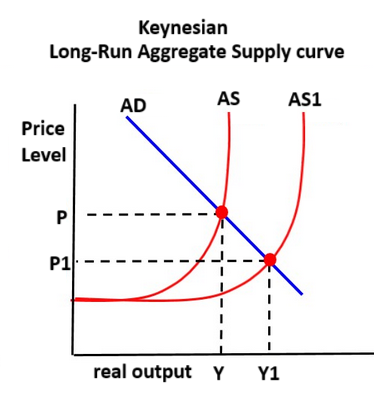

Keynesian LRAS Curve

The Keynesian LRAS curve is typically shown as horizontal at low levels of output, becoming upward sloping as the economy approaches full capacity.

Characteristics of the Keynesian LRAS Curve:

- Flat at Low Output: In the early stages of economic growth, there is a lot of unused capacity in the economy (such as underemployed workers or idle capital). The economy can increase output without causing inflation, so the LRAS curve is horizontal at low levels of output.

- Upward Sloping at Higher Output: As the economy approaches its full capacity, resource constraints (e.g., labour shortages, capital limitations) begin to limit further production. At this stage, increases in output can only be achieved by higher costs, leading to inflationary pressures. Thus, the LRAS curve slopes upward.

- Relevance to the UK Economy: The Keynesian model suggests that in times of recession or economic slack, the government can increase demand without causing inflation, as there is underutilised capacity in the economy.

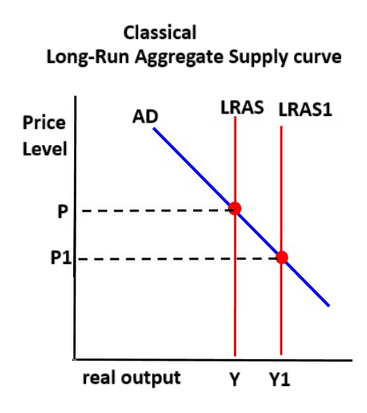

Classical LRAS Curve

The Classical LRAS curve is typically shown as vertical, reflecting the belief that, in the long run, output is determined solely by the economy's productive resources (labour, capital, and technology), and is independent of the price level.

Characteristics of the Classical LRAS Curve:

- Vertical Line: The Classical model assumes that the economy is always at full capacity in the long run. As such, changes in the price level do not affect the total output because all resources are fully utilised. The economy’s potential output is determined by factors such as labour, capital, and technology.

- Full Employment: The Classical view assumes that in the long run, the economy will always operate at full employment, meaning that any increase in aggregate demand will result in higher prices (inflation) rather than an increase in output.

- Relevance to the UK Economy: The Classical model emphasises the importance of supply-side factors in determining the economy’s potential output and suggests that market forces (without government intervention) will ensure that the economy returns to its full capacity in the long run.

Comparison of the Keynesian and Classical LRAS Curves

| Feature | Keynesian LRAS | Classical LRAS |

|---|---|---|

| Shape | Horizontal at low output, upward sloping at higher output | Vertical at full employment (potential output) |

| Output Level | Can increase without inflation at low levels | Fixed at full capacity, regardless of price level |

| Economic Assumptions | Unused capacity exists, demand management can boost output | Full capacity and full employment are always achieved in the long run |

| Policy Implications | Government intervention can stimulate output when there is slack | The economy self-adjusts, minimal government intervention needed |

Factors Influencing Long-Run Aggregate Supply

Long-run aggregate supply is influenced by changes in the economy’s productive capacity, which can be affected by several key factors:

Technological Advances

- Impact on LRAS: Technological progress can lead to improvements in the efficiency of production, enabling the economy to produce more goods and services with the same amount of resources. This shifts the LRAS curve to the right, indicating an increase in the economy’s potential output.

Example: The introduction of automation in manufacturing can reduce production costs and increase output, expanding the economy’s capacity.

Changes in Relative Productivity

- Impact on LRAS: Changes in productivity (the amount of output per unit of input) in various sectors of the economy can influence LRAS. If certain industries or sectors become more productive, the overall productive capacity of the economy increases, shifting the LRAS curve to the right.

Example: If workers in the technology sector improve their productivity due to better tools or skills, this can increase overall output, shifting LRAS outward.

Changes in Education and Skills

- Impact on LRAS: The level of education and the skills of the workforce are key determinants of long-run economic capacity. Improvements in education and training lead to a more skilled workforce, which can increase productivity and shift the LRAS curve to the right.

Example: Increased investment in education, such as higher rates of participation in higher education or vocational training, can improve the skill set of the workforce, enhancing productivity and increasing the potential output of the economy.

Changes in Government Regulations

- Impact on LRAS: The regulatory environment can affect the economy’s ability to produce. Deregulation (removing unnecessary restrictions) can increase competition, reduce costs, and encourage investment, thus increasing potential output and shifting the LRAS curve to the right. Conversely, overregulation can limit business activities and reduce the economy’s capacity to grow, shifting the LRAS curve to the left.

Example: A reduction in business regulations (such as fewer restrictions on setting up new businesses) may encourage innovation and investment, expanding the economy’s productive capacity.

Demographic Changes and Migration

- Impact on LRAS: Changes in the size and structure of the population can significantly influence the supply of labour and capital, which in turn affects long-run aggregate supply. An increase in the working-age population, due to factors like migration or a rising birth rate, can increase the economy’s productive capacity, shifting the LRAS curve to the right. Conversely, an ageing population can reduce the labour force and shift LRAS to the left.

Example: High levels of immigration can increase the supply of labour, enhancing the economy’s productive capacity and shifting the LRAS curve outward.

Competition Policy

- Impact on LRAS: Effective competition policies can improve the efficiency of markets by reducing monopolies and encouraging firms to innovate. A more competitive environment can increase productivity and lead to a higher level of potential output, shifting the LRAS curve to the right.

Example: Anti-monopoly laws that break up large, inefficient companies can lead to greater competition, encouraging firms to invest in better technologies and improve productivity.

Summary of Key Points

- The Keynesian LRAS curve is horizontal at low levels of output and upward sloping as the economy reaches full capacity. The Classical LRAS curve is vertical, reflecting the belief that in the long run, output is determined by the economy’s capacity and is independent of the price level.

Factors influencing LRAS include:

- Technological advances, which improve efficiency and increase potential output.

- Changes in relative productivity, which enhance the economy’s capacity to produce more goods and services.

- Improvements in education and skills, which raise the productivity of the workforce.

- Changes in government regulations, with deregulation potentially increasing productive capacity.

- Demographic changes and migration, which can expand or contract the labour force.

- Competition policy, which encourages innovation and efficiency in markets.

Understanding these factors helps in analysing how an economy’s long-run potential output can evolve and how policies can influence that growth over time.